TeorMinimumEval

The Theoretical Minimum is an exam designed by Lev Landau to assess student's understanding of physics. L.Landau regarded it as the "minimum" necessary to begin serious work in theoretical physics, and required it for entry into his elite seminar and research school. Since its introduction in 1933, only 900 students have succeeded.

TeorMinimum-Eval aims to approximate¹ Landau's Theoretical Minimum as an evaluation benchmark for AI systems.

TeorMinEval-Quantum v.1, pass rate by category

Contributors

Supported by

This research was supported in part by Lambda, Inc. Training was done using Tinker by Thinking Machines.

What are we trying to do?

We argue that current physics benchmarks primarily test pattern recall rather than true understanding. TeorMinimumEval seeks to reconstruct Landau's Theoretical Minimum exam - one of the most challenging tests of genuine understanding - as an evaluation benchmark for AI.

This evaluation stands out because:

1) We source problems that, to the best of our knowledge, were not used for mid or post training of foundational models yet.

2) We design scoring systems that assess not only answer correctness, but also critical aspects such as intuition, progress, hypothesis generation, elegance, and other process-based rewards.

Our goal is to produce a dataset of identified physics hallucinations and reasoning failures, create an RL environment for training on high-quality tactics and problems, and, in the long term, develop better AI assistants for teaching and research.

Latest News

- Oct 6First release with 322 quantum mechanics problems

- Oct 7Added 31 problems in math, mechanics, and field theory

- Oct 16Added 690 problems and 690 solutions in quantum mechanics

- Oct 18TeorMinEval-Quantum v1 published

- Oct 22TeorMinEval accepted for private beta of Tinker by Thinking Machines.

- Oct 24TeorMinEval won a compute grant from Lambda, Inc.

Dataset

An oscillator of mass $m$ and frequency $\omega$ is in a ground state. Suddenly the frequency changes to $\omega'$. Find the probability of transition to an excited state.

TM-QM-L-3Find: 1) Born scattering amplitude for a slow particle on a potential which decays as $\lambda/r^3$ at infinity. 2) Scattering cross-section.

TM-QM-L-6| Category | Problems | Answers | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Theory | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Math 1 | 15 | 12 | 2 |

| Math 2 | 12 | 7 | 7 |

| Mechanics | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Quantum Mechanics | 1003 | 693 | 690 |

| Quantum Electrodynamics | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Statistical Physics I | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Continuum Mechanics | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Electrodynamics of Continuous Media | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Statistical Physics II | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Physical Kinetics | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 1035 | 716 | 702 |

Reward Structure Example

Compute the probability P for a quantum two-level system to be in the excited state at t → +∞, if for t → -∞ it was in the ground state.

Human baseline

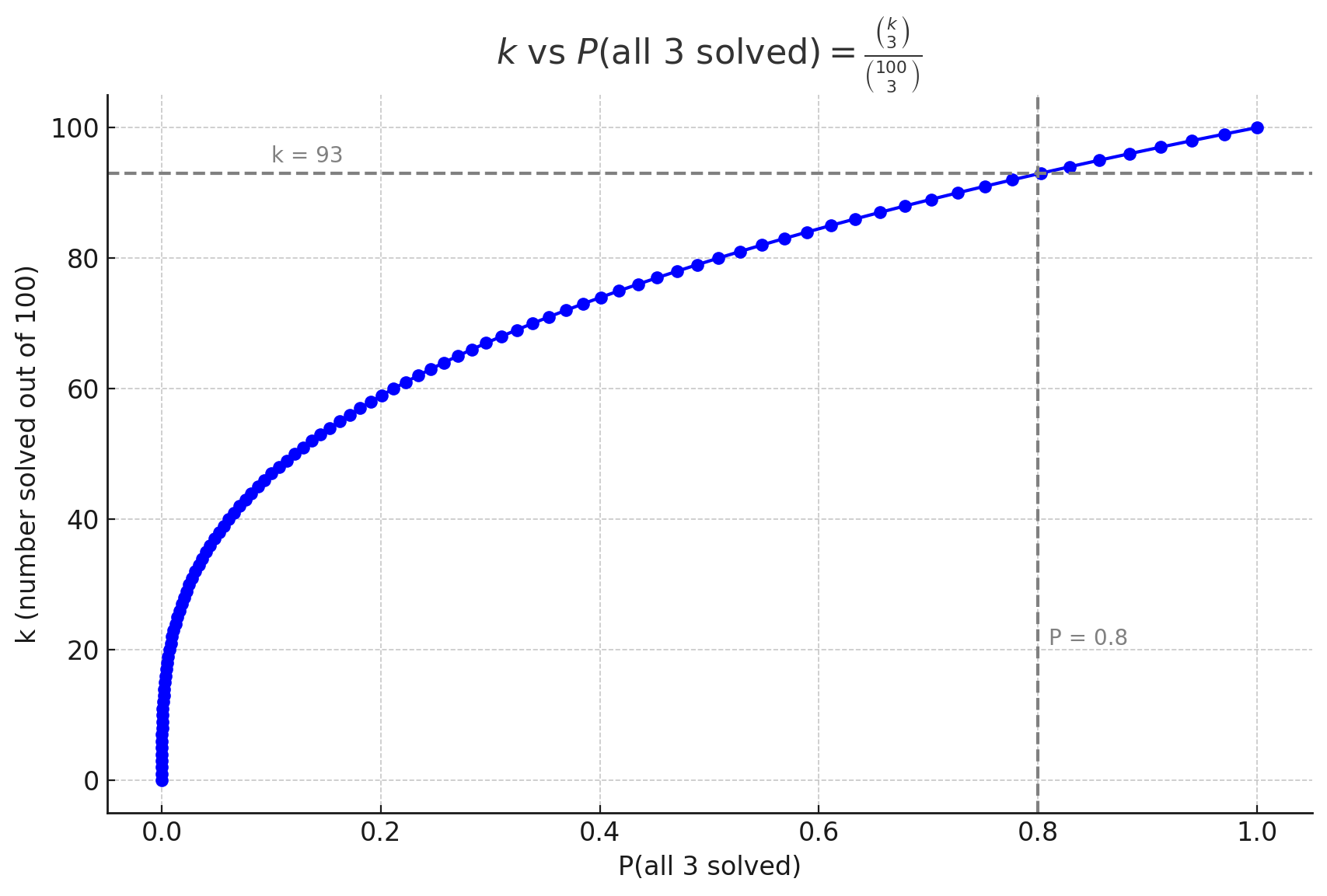

To pass the exam, the student must solve 3 problems. Assuming that before the exam, due to gossip and so on, the student expects a pool of about 100 problems, and that the problems are chosen uniformly at random without replacement, the number of problems they should know depends on their target confidence of passing:

We ran a poll and found that the average student will show up for the exam only if they are 80% confident of passing. The corresponding value is ( k = 93 ). Thus, our baseline is 93% accuracy.

Other notes

Inference costs

One sweep on 1000 quantum mechanics problems is ~60$ in gpt-5 compute. We'll start working on a lighter version of the eval once we finish making this one as comprehensive and hard as possilbe, and we'll publish it once there will be evidence that it will be just as challanging as the full one.

If you are an inference provider and are able to sponsor compute consider sending a note to: savelii.kho@gmail.com

Motivation

This eval is part of a larger project to improve AI’s ability to learn principles of problem solving and scientific research that *actually generalize*. We believe current AI models don’t yet exhibit that ability, and we want to understand how to train them so they do. One way that ability shows up is in how a student solves problems — which motivated our work on better evals and more convenient annotation infra.

This eval differs from existing ones in several ways. First, it includes a private collection of hard and beautiful problems that almost never appear in other benchmarks. Second, and maybe the most important, it scores AI systems not only on the correctness of the final answer (often a formula) but on many other metrics of progress. This is motivated by real academic evidence: a good problem can teach a student a lot once they spend enough time with it. Any well-educated scientist knows it’s not only useful to get the right answer, but also to see how one problem connects to another, what methods it demonstrates, where it comes from, what tactics work, which parts of the solution are creative and which are mechanical. On real exams, students can usually take their time with mechanical work (like integrating or simplifying), where typos are easy, but are rewarded much more for good intuition, elegant reasoning, and insight.

A modified version of this eval naturally becomes an RL environment.

After we finish **TeorMinimumEval**, we’ll start working on an eval tuned for practical experimental physics — starting with solid-state physics, materials design, and superconductivity.

Real exams are more than just writing down solutions and getting a score. They’re a collaboration between the student and the examiner that often drifts away from the original problems into follow-up questions, new tasks, sometimes even the whole curriculum — and can last for hours. Figuring out how to approximate this kind of human-human interaction using chain-of-thought solvers, self-critique, LLM-as-judge setups, verifiable rewards, or other mechanisms is an open area of study and experimentation.

Back to textOf course, a lot of engineering and research has already gone into training models that generalize well — with some empirical evidence (like double descent) and theoretical grounding (compression, symmetries) supporting it. What we’re talking about is how to keep improving on top of that, possibly by leveraging new empirical findings such as scaling laws in test-time compute and RL compute, together with better datasets and new environments.

Back to textExactly how much this dataset is “polluted” or overlaps with other benchmarks hasn’t been carefully analyzed yet, but it’s important to understand — and that work is in progress.

Back to textCitation

@software{Kholin2025TeorMinimumEval,

author = {Savelii Kholin and David Saykin},

title = {TeorMinimumEval: A Benchmark for Evaluating AI's Understanding of Physics},

year = {2025},

version = {0.1.0},

doi = {10.5281/zenodo.xxxxxxx},

url = {https://github.com/asapsav/TeorMininumEval},

note = {Available at GitHub. MIT License.}

}